On Instagram, Orthodox Women Find a Voice – and Power

The social media site has given ultra-Orthodox women a following unmatched by the all-male Chief Rabbinate. ‘The rabbis don’t have that same engagement,’ says one. ‘They don’t have 20,000 people in their shul!’

By Rivkah Brown, published Oct 21, 2019 12:11 PM on Haaretz

There’s nothing remarkable about Chany Rosengarten’s Instagram account. If anything, it’s a textbook of Insta-influencer tropes. There are OOTD (outfits of the day) and QOTD (quotes of the day), giveaways and Q&As, family portraits and food shot from above. And there is impossibly perfect hair. What’s remarkable is that Rosengarten, who grew up in a community that crusades against the internet, now makes a living from it.

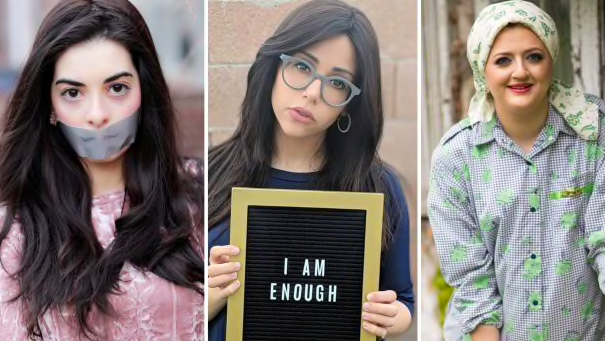

From left: Adina Sash, Bari Mitzmann and Chany Rosengarten. Credit: Instagram

Rosengarten was born in New Square, New York, the state’s poorest municipality and one of its richest centers of Hasidic life. Its name is an anglicization of Skver, the Ukrainian town from which its founders — including Rosengarten’s great-grandparents — arrived in 1954. These days, New Square is known for putting the “ultra” in ultra-Orthodox, most famously with gender-segregated sidewalks. Like every other ultra-Orthodox community, New Square is organized around the authority of a rebbe. Yet even for a Hasidishe rebbe, David Twersky exercises remarkable authority. Skverers must seek his permission for many day-to-day activities, such as applying for a driving license (prohibited for women) or moving neighbourhoods (compulsory if marrying out of the Skverer community). Twersky has been said to enjoy near-divine status; Skverers hold a weekly tish (“table” in Yiddish) ceremony at which they sing and pray while the rebbe eats. With a chauffeur and multimillion-dollar vacation home on the Hudson River, Twersky is, if not deified, at least living the high life.

Chany Rosengarten preparing challah in a picture she posted on her Instagram account. credit: Instagram

Rosengarten’s parents raised her and her 10 siblings to typically stringent Skverer standards. Preparation for Passover took weeks. The leavened grain is forbidden during the holiday, yet the Rosengarten’s went the extra mile, banning processed food of any kind from the house. Rosengarten delighted in her family’s devoutness. Speaking to me on the phone from her home in Monsey, a 20-minute drive from where she grew up, her voice brightens as she tells me about helping her mother make a simple syrup to substitute refined sugar. “Our life revolved around Judaism,” she trills. “I never questioned any rules. In fact, I found them exciting.”

However, there was one rule with which, as she got older, Rosengarten kept colliding. She became a writer and wanted to learn how to promote her work, so she enrolled in a marketing course. Her instructor gushed about a new site called Facebook. “I felt horrible about it,” Rosengarten says. “I knew that the community spoke against it — but I opened an account, just to figure things out.” Her internet exploration was short-lived. After friending a bunch of people, she began receiving “creepy messages.” She recalls, “I was like, ‘If this is what Facebook involves, I’m out of here.’”

But when Rosengarten’s first novel, “Promise Me, Jerusalem,” was about to be published in 2017, she found herself facing the same dilemma: “People told me the best way to market a book these days, the best way to market anything, was on social media.” What persuaded Rosengarten to return to the breach was that since her failed Facebook foray, a kosher platform of choice had emerged: “They were saying that the Orthodox community had taken to Instagram.”

So they had. Since the platform’s founding in 2010, Haredim (mostly women, mostly in America) have been steadily flocking to Instagram — exactly how many it’s unclear, though hashtags give a helpful indication. Like the rest of Instagram, frum (“religious” in Yiddish) Instagram centers on food and fashion, #tznius or “modest” clothing (50,000 posts) and #koshercooking (36,000). There’s the food blogger whose kugel racks up five-figure likes, the modest fashionistas whose “Morah” (Hebrew for “teacher”) skirt covers Hasidic knees everywhere. In between is a vast constellation of parenting gurus, sheitel machers (wig stylists) and mitzvah motivators. It’s a world you wouldn’t know existed unless, like me, you went looking. Though some frum accounts are beginning to trickle into the mainstream — notably that of Adina Sash, aka Flatbush Girl — the vast majority serve an exclusively frum audience. For the most part, Haredim are as insular online as offline.

An image Adina Sash posted to Instagram featuring herself as Wonder Woman. Credit: Adina Sash's Instagram account

Rosengarten reckons the platform’s appeal to frum women, at least in the beginning, was its comparatively limited functionality. “When I first went on Instagram,” she tells me, “I found it to be very good, clean experience. It didn’t have ads then; I could choose what content was given to me. If I only wanted to see other Orthodox women, I could.” Unlike Facebook or, worse still, Twitter, Instagrammers could only post and like photos; comments and direct messages were but a distant dream. The platform has since lost its innocence, yet frum Instagram continues to flourish. Why?

In the beginning was the blog. In the early 2000s, the J-blogosphere began taking shape. Under aliases ranging from the descriptive (The Girl or SH — Stamford Hill, an ultra-Orthodox neighborhood in north London) to the provocative (Hasidic Feminist) to the borderline blasphemous (Failed Messiah), thousands of ultra-Orthodox Jews from across the world (though predominantly London and New York) would kvetch about their communities. Their remarks spanned from lighthearted sartorial critiques (“Real Chassidim [sic] don’t have dents on the side of their hats. Only Lubavitchers do”) to stinging rebukes of sexual abuse within the Rabbinate. Yehudis Fletcher, who blogged as Fluffy Kneidle (Cockney rhyming slang for aidel maidel, “sweet girl” in Yiddish), remembers an insatiable audience. “The comments would run into the hundreds,” she tells me over Skype from her home in Manchester, England. Though initially an underground movement, J-blogs gradually became part of Jewish popular culture: For years, London-based weekly The Jewish Chronicle ran a Best of the Blogs column.

By 2009, the J-blogosphere had all but deflated, as readers and writers migrated onto social media. The transition wasn’t smooth. Essential to the success of J-blogs was the anonymity they afforded. Almost all J-bloggers used a “nick,” or nickname, cultivating what Andrea Lieber, professor of religion at Dickinson College in Pennsylvania, calls a “private-public” space, one in which Haredim could collectively air grievances without fear of communal repercussions. By contrast, new online platforms not only encourage you to build a profile around your (at least apparently) real identity, but also feed a cult of personality. Visual platforms like Instagram leave even fewer places to hide.

The end of the era of anonymity split the J-blogosphere in two. On one side were Shulem Deen, a Skverer, and Deborah Feldman, from the Williamsburg-based Satmar sect, who outed themselves, left their communities and converted their J-blogs into the bestselling memoirs “All Who Go Do Not Return” and “Unorthodox.” On the other were the silent masses who logged off and dropped out, fading happily into obscurity. “They had thinking to do,” Fletcher says of this second camp. “They did it, came to a decision, then” — like Amish teenagers returning from rumspringa — ”got married and continued living their life.” The rule of thumb was: If you wanted to stay frum, you kept shtum (Yinglish saying (yiddish+english), in English it translates to: if you want to stay orthodox, you kept quiet).

Many of the frum women who use Instagram do so anonymously. But just as many not only name themselves, but attempt to make a name for themselves on the platform. When did being openly online become acceptable within the ultra-Orthodox community? In some sects, it always was. Chabad, for example, sees the web as another tool for intra-faith evangelism. In the rest of the Haredi world, attitudes have softened over time. The wild success of J-blogs and advent of social media have made the internet a fact of frum life: a 2016 study found that ultra-Orthodox Jews in Israel spent just as much time online as the rest of the population (albeit more covertly: Their internet usage peaked late at night). In response, Israel’s Chief Rabbinate has been forced to loosen its grip, with some rabbis giving special dispensation for internet use, for instance for business purposes. But even those with staunchly anti-internet rebbes have found safety in numbers: You can’t punish everybody. “The cat’s out of the bag,” says Sash via a WhatsApp call from — where else? — Flatbush. “The rabbanim lost the war on the internet.”

As the medium has changed, so has the message. J-blogs took on the salty, bilious flavor of the rest of the blogosphere. The smokescreen of anonymity and headrush of internet access emboldened J-bloggers to speak about Haredi life frankly, even critically. Instagram, by contrast, is aspirational by design. Its built-in image editing and mood board-style layouts incentivize users to curate and exhibit their lives as artwork. “Priority goes to the people who show certain things,” says Rosengarten — things like just-woven wigs and freshly-baked challot, perfect marriages and photogenic children.

Then there’s the question of money. J-bloggers didn’t try to make any; Instagrammers openly do. Like their secular counterparts, frum Instagrammers monetize their pages primarily through sponsored content. This means the promotion — in more than one sense — of a Hasidic lifestyle, be it a trending modest fashion brand or a newly-opened kosher deli. “Two years ago,” Rosengarten recalls, “it was [Brooklyn kosher ice creamery] Urban Pops. Ordering Urban Pops for your simcha became a kind of social status.” If the blogosphere enabled Haredim to question their conservatism, Instagram encourages them to compete at it.

Bari Mitzmann, who posts about modest fashion, motherhood and mindful living. Credit: Bari Mitzmann's Instagram account

Bari Mitzmann’s page began life as an tznius fashion blog. “I wanted to show that you can look funky, confident and cute, while still covering the parts that need to be covered,” she tells me over the phone from her home in Las Vegas. Mitzmann’s early posts showcase her long, glossy wigs, tall, handsome husband and seemingly infinite wardrobe. Over time, however, Mitzmann tired of projecting perfection. “I realized I was trying to keep up this Instagram persona after giving birth,” she says, “so I opened up to my followers.” She began interspersing the selfies and #sponcon with stories of postpartum depression and Lyme Disease, conditions she had been suffering with silently — and a small corner of the internet broke. “People went nuts,” Mitzmann recalls. “They were like, ‘Thank you for not being a superhero. Thank you for being normal.’” Mitzmann’s story is allegorical of Instagram’s. “First Instagrammers needed a nice life,” observes Rosengarten. “Then there was this wave of realness.” Authenticity is the new name of the game.

At first, the struggles Mitzmann shared — with motherhood, physical and mental illness — were universal. It wasn’t long, however, before Bari’s “realness” inspired her audience to be up-front about their “spiritual suffering.” One woman told Mitzmann that she was finding ultra-Orthodoxy so hard that if it weren’t for her son’s place at a prestigious yeshiva, she’d have left years ago. This was the last thing Mitzmann wanted: As a ba’alat teshuva, someone who wasn’t raised Haredi but rather chose it, Mitzmann sees it as her mission to encourage other Jews to become more Orthodox, not less so. So in the spirit of mutual motivation, she began sharing her own difficulties with Halakha (Jewish religious law).

Poolside tsniut (modesty) with Bari Mitzmann. Credit: Bari Mitzmann's Instagram account

In one post, Mitzmann wrote about how hard it is to stay tznius at the pool. Her intention, she says, wasn’t to undermine halakha: “I wasn’t going to dress less modestly — that’s not an option for me.” Instead, she wanted to tap into her Instagram following to crowdsource a solution to the problem of poolside tzniut — “styles of loungewear that were both modest and will keep you cool.” (Though some needed a few modest-making alterations; thankfully, she says, “there’s nothing a sewing machine can’t fix.”) The poolside cover-ups are now grouped on Mitzmann’s Instagram, “in the hopes that if somebody else is struggling some day, I can provide a resource.” These days, Mitzmann sees her page as “a community of acceptance and realism.” Mitzmann has created a space for women to share the strain of ultra-Orthodox observance — but ultimately, to reinforce their commitment to it.

Yet if Instagram has facilitated collaborative conversations about Jewish life and law, it’s also fostered individualism. The increasing self-centeredness of Western culture has long threatened to destabilize ultra-Orthodoxy’s collectivist foundations. It’s a threat that’s been redoubled by the internet, which has opened the eyes of many Haredim to other ways of living; to the possibility, as J-blogger The Shaigetz put it, of “Doing it maai vey.” Instagram tripled this threat. The platform has completed the reification of individual identities, giving birth to the “influencer.” The Oprahtic doctrine of self-actualization is one Chany Rosengarten routinely preaches: “Be free to be you,” proclaims a motivational quote pic on her page; “Your identity is your freedom,” declares another. “When we [women] start owning just how magical we are,” reads one of her captions, “that’s when we really start living our best life.”

Yet New Age platitudes take on new meaning in Rosengarten’s mouth. Her promotion of individual agency jars with the conformity her community demands. It’s a conflict she explicitly addresses in one post:

“I was considering the repercussions of expectations, today. How in the culture I grew up, being a ‘balabusta’ [good homemaker] is right up there in ideals with the highest values, and for women with other ambitions, forging an identity is a re-negotiation process with themselves. ... Take that with you. Because if you are a woman, a person, you will always renegotiate who you are, who you want to be, and who you tell yourself you SHOULD be based on years of societal programming. If you want, you can choose to discover yourself anew. Personal Power is the ability to choose.”

Here, the appeal of Instagram to Haredi women begins to make sense. Its rampant individualism provides a welcome antidote to a community that has, according to Mitzmann, “totally forgotten about the individual.” By focalizing the individual experience, it’s given Haredi women an opportunity to discover themselves beyond wife- and motherhood, and to decide how to situate themselves within ultra-Orthodoxy. Sash puts it more bluntly:

“It’s like someone said about the #MeToo movement, that it’s almost like women have been these bottled up bees, and all of a sudden it’s this explosion of venom. And I feel like this thing that Orthodox women are catching through social media is like, ‘Oh, my gosh, we’ve been taking it and we’ve been taking it. And I’m done taking it.’ It’s this explosion of like: Don’t tell me what to wear. Don’t tell me how to dress. Don’t tell me how to talk. Don’t tell me what music I can listen to. Don’t tell me if I’m allowed to cover my knee, don’t tell me if I’m allowed to cover my elbow. Don’t tell me if I’m being too sexy. Don’t tell me if I’m being too provocative. I’m going to do whatever the hell I want.”

In April this year, Rosengarten took her own advice. Most people couldn’t have told what made that day’s selfie different from the hundreds of others — though Rosengarten’s followers would’ve registered it instantly. It was the gleaming Cadillac. The post signaled her decision to drive, “which is not a norm in the community” (in fact, it’s forbidden). Rosengarten was creating a new norm — a process which, though by definition unorthodox, she sees as firmly in the spirit of Judaism. “Judaism is not a religion that cannot withstand questioning,” she tells me. “Judaism is actually steeped in questioning, in finding God, in deciding where you fit within all that stuff.” This, it seems, is the defining difference between J-bloggers and frum Instagrammers. Whereas most J-bloggers led a double life — an offline, conforming one and an online, questioning one — Instagram has enabled frum women to integrate their ambivalence. The word Rosengarten uses most often to describe her decision to drive is “whole.” She was exercising personal power.

Chany Rosengarten. Credit: Chany Rosengarten's Instagram account

Yet the process was a tougher one than Rosengarten’s Instagram made it appear. It took her almost three years to bring herself to apply for a license. “My question was not whether it was right in the community’s eyes” — that was obvious — “but whether it was right for me.” This didn’t mean there weren’t communal consequences to face. In New Square, the price of individualism is alienation. Once word of Rosengarten’s driving spread, she was forced to pull her kids out of their New Square schools. Reflecting on her decision, Rosengarten sounds a note of regret. “Maybe it was a mistake, and I can retrospectively say I would have wanted to adhere to community standards. I don’t know. Like, if I ever need to go back on that decision and say, ‘You know what, I messed up,’ I’m OK with that. I’m OK failing.”

When I ask Rosengarten why she publicized her decision to drive — did she want to encourage other Skverer women to do the same? — she balks. “Changing the [halakhic] standards is not my business at all,” she insists. “I’ve decided for myself how to live my life, and it’s not the way I want other people to live their theirs.” In this way, individualism is at once a risky position and a safe one. By insisting she’s a mere individual rather than an influencer, Rosengarten makes her actions seem less subversive.

Indeed, Rosengarten resolutely resists critiquing her community. She sees ultra-Orthodox women’s unfreedom as the product not of social forces, but of individual choices: “I’m not buying that about women being subjugated. We are not, but we can choose to be. ... I chose to make my life good.” Sash sees things differently. While she too has used Instagram to experiment with individual observance, for example, by wearing short sleeves, she is open about her ambition to make change on a macro level within the frum community. In 2017, Sash launched the campaign #frumwomenhavefaces. “Let it be known,” she battle-cried to her followers, “that your voice is louder than the extremists who have weaponized & twisted the words of Kol Kvoda Bas Melech Penima.” Translated as “The glory of the daughter of the king is within,” the biblical proverb has about is often the first recourse of rabbis wishing to justify the censoring of women in ultra-Orthodox print media, and Sash was reinterpreting it.

Her campaign invited frum women to repopulate their media with their own images, manifest their glory not by hiding their faces but by showing them. Unlike Rosengarten, Sash’s aims are overtly political (indeed, she recently made a bid for New York City Council). She is only half-joking when she compares Instagram influencers to Orthodox rebbes: “Each influencer has their Hasidim,” she says. “The rabbis don’t have that same engagement. They don’t have 20,000 people in their shul!” A recent competition on her Instagram page played on this analogy. To enter, you had to post a photo of something Rebbe Adina would consider kosher, overlaid with a custom-made Flatbush Girl seal of approval. Sash may not actually be setting herself up as a rabbinical authority, but she is entirely serious about using Instagram to reinvest frum women with both personal autonomy and collective authority.

Bari Mitzmann can’t sing. In fact, she sings beautifully; it’s just that the Halakhic Law of Kol Isha (Jewish Law of pertaining to women’s voices) prohibits anyone except her family from hearing it. As a drama kid, Mitzmann found Kol Isha hardest of all the religious rules to embrace when she became Orthodox (if she hadn’t, she’s convinced she would have had her own Disney Channel show by now). Instagram offers a workaround: “I can’t sing, but I can use my voice.” Frum women sound different on Instagram: some progressive, others conservative. But the chorus they constitute sounds radical to me.